Fire

Fire has long been recognized as a major hazard following earthquakes. Before the 20th Century, earthquakes would often upset burning candles, lamps, stoves and fireplaces (with dangerous fuels common). Today in the US. ruptured gas lines and arcing electrical wires are the most common sources of ignition. In addition to providing chances for ignition, earthquakes can block access to fire fighting equipment, and damage fire-fighting water supplies, making fighting the blazes, of which there might be many across a city, especially challenging.

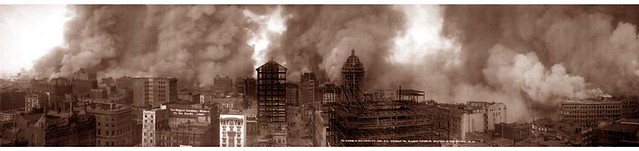

The most famous earthquake-initiated fires in US history burned much of the City of San Francisco in 1906. Up to 90% of building damage, after the earthquake, was attributed to the fires and the crude firefighting techniques employed in an effort to contain the blaze.

More recently, the 1995 Kobe, Japan Earthquake highlighted the danger of urban fires following earthquakes. Hundreds of fires broke out following the quake and automobile congestion and debris blocked many streets. Of the thirty reservoirs available to Kobe, 22 had seismic shut off valves to conserve water for firefighting. These all worked but massive damage to piping systems and the road congestion made it very difficult to access these reserves. Kobe had also invested in 968 cisterns with ~ 40,000 gallon capacity, about a 10 minute supply for a pumper truck. But, the combined underground water system was depleted in 2-3 hours leaving only tanker trucks to carry water from the bay. The fires consumed a combined area of 4,500 square meters and 5,500 buildings were lost to the fires.

Fire also complicated response to the 1989 Loma Prieta Earthquake in the San Francisco Bay Area.

When Pacific Northwest urban areas exercise earthquake response plans, fire departments are usually major players. However, because we have not had a large earthquake since 2001 this recent preparedness work remains untested.