Summer rockfall time, yet again

This blog UPDATED on Sep 14

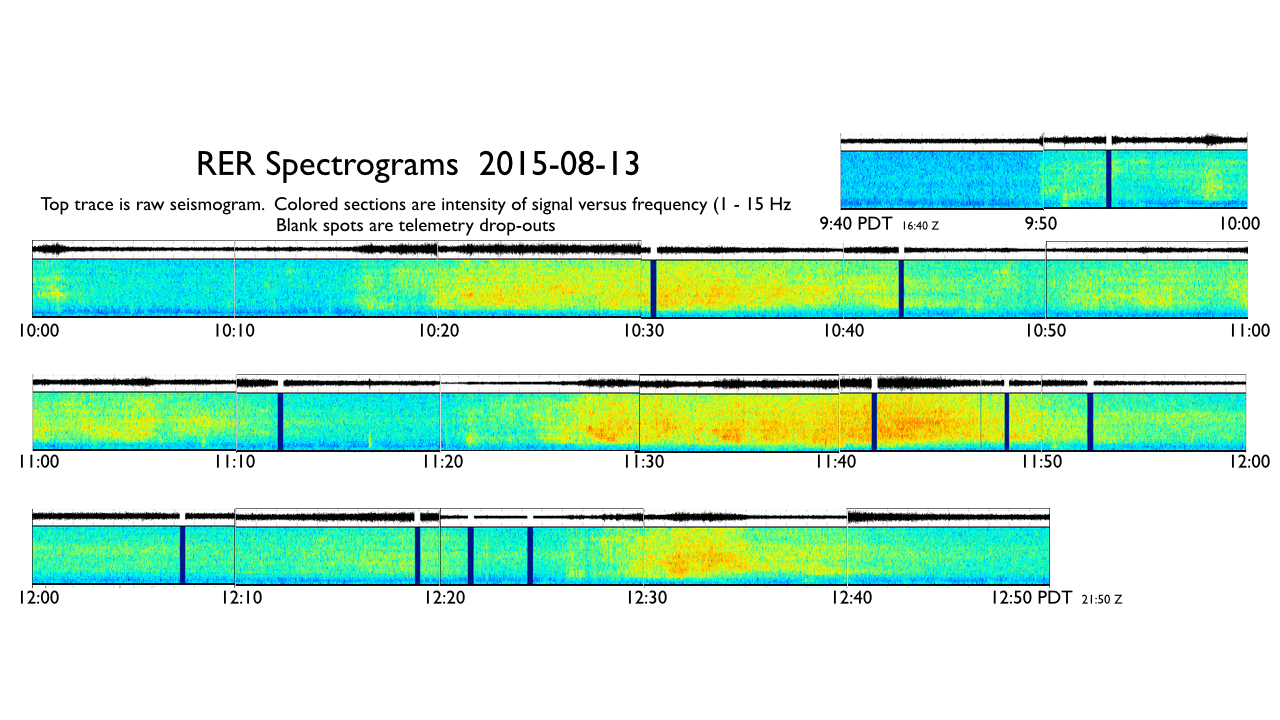

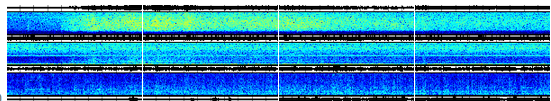

On Aug 13, 2015 the seismic station, RER (Emerald Ridge ~ 350m from Tahoma Creek) at Mount Rainier showed signals consistent with a small debris flow in Tahoma Creek. Reports from Rainier National Park confirmed this. The Cascade Volcano Observatory has a short description of this event in their 2015 News Briefs. This debris flow (muddy flood containing rocks, trees and other debris) was likely started by a jökulhlaup from the terminus of South Tahoma Glacier. There were several 'pulses' of the flood over the course of about three hours. A pasted together set of seismograms/spectrograms starting at 9:40 PDT clearly shows the changes in shaking probably reflecting different volumes of water being released.

The warmness of the color is proportional to the strength of ground shaking at any given time. The vertical axis is the frequency of that shaking. Note that for these debris flow events the shaking takes place at all frequencies but most intensely in the 4-10 Hz band. Mount Rainier National Park provides many areal photos of the debris flow source and drainage and a very nice Press Release with other details.

Such debris flows were fairly common in the South Tahoma drainage in the 1990s up to the early 2000s. Here is a partial report on the seismic recordings of such a debris flow in August, 2001.

Other Cascade volcanoes have had recent debris flows as well. A recent one at Mount Baker took place in June, 2013, though this one may have had an avalanche origin rather than a jökulhlaup source.

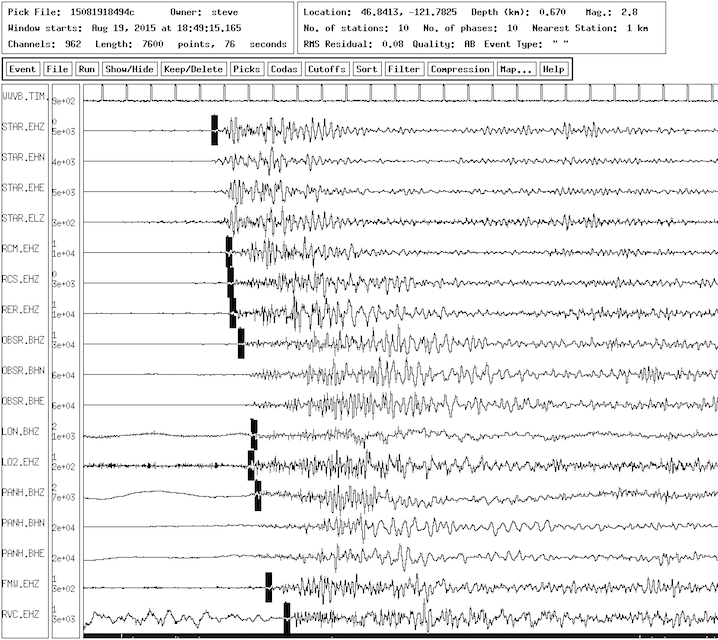

Rock falls are yet another seismic source common on volcanoes. On Aug 19, 2015 at 11:49:53 AM PDT a seismic event at Mount Rainier fooled the PNSN automatic event detection and location system to thinking a Magnitude 3.2 earthquake had taken place. Since we never trust our computers to get things always right we quickly reviewed the seismic trances by eye and recognized the event to be a large rock fall, not a traditional earthquake (due to fault breakage). Since this event started rather abruptly (which is not always the case) we could time seismic arrivals quite precisely and got a pretty good location. Here are the set of seismograms from many stations located on Mount Rainier for this event.

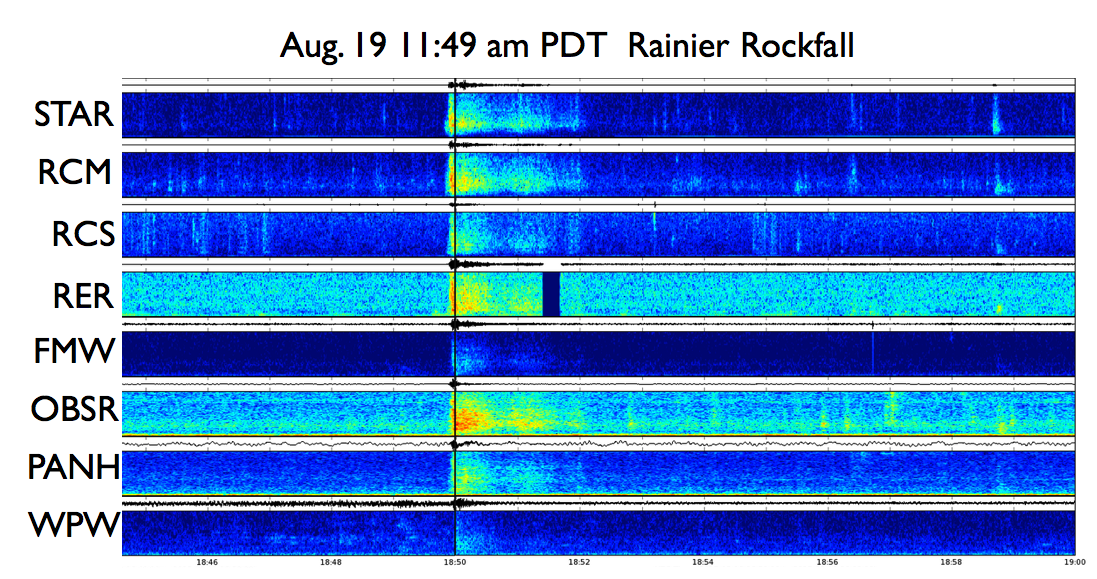

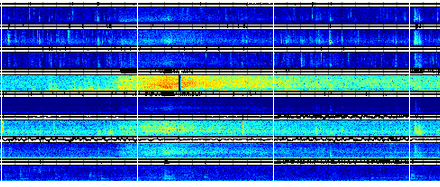

The black rectangles on each trace are our estimates of the arrival time of the main P-arrival used to locate the event. Here are the spectrograms for some of the same stations.

Note that the strong signals are much shorter in duration than for the debris flow mentioned above. The strong part lasts for only 10-15 seconds and the whole thing is over in less than two minutes. However, unlike the debris flow that only recorded on a station very nearby this event is recorded all over the mountain and even as far away as White Pass.

Different people picking the seismic arrivals and using different location algorithms all come up with locations very close to the same place as shown in the following oblique Google image.

The orange markers are location estimates done by different people/techniques for the same event. Stars are the nearby seismic stations. Queries to the staff at the Park resulted in the Park Geologist, Scott Beason recognizing what he thought was a rock fall scar on or near the Success Cleaver, very near our location estimate. Scott provided the following photo taken from some distance. The arrow is pointing to the apparent rock fall scar.

This event was no where near as large as several rock falls from Nisqually Cleaver in the summer of 2011.

Avalanches can have somewhat similar seismic signals but generally do not last as long as a debris flow signal but longer than a rock fall. Ice avalanches are fairly common during winter and spring. Of course large landslides such as the Oso event of March, 2014 are a very different story.

Update as of Sep 14, 2015 As the summer goes on with alternating hot weather and rain it seems that there have been other small debris flows both at Mount Rainier and at Mount Hood. Scientists from CVO reported on Aug 24, 2015 that there was obvious evidence of recent high flows in the White River off of Mount Hood. Seth Moran of CVO scanned seismic records of Mount Hood stations and reported: "what look to be robust debris flow signals (emergent, gradual onset, relatively high frequency (5-10 Hz) and extended duration) on PALM and TIMB going as far back as 08/11. Signals can be seen on 08/12, 08/13, 08/19, 08/20, 08/22, and 08/23, with all events occurring in the afternoon and/or evening. The largest and/or longest-lasting events occurred on 08/19 (1405-1715 PDT, several pulses contained within) and 08/20 (1345-1445 PDT)." Here is a set of spectrograms from 02:00 to 02:40 Z on Aug 21 for stations PALM, TMB and HOOD showing, in particular on PALM the debris flow signal peaking around 02:10 Z.

On Sep. 12, 2015 Scott Beason, Mount Rainier National Park Geologist, reported getting a call regarding someone hearing noises high in the South Tahoma Glacier area. Reviewing spectrograms for several days around this time we find evidence of pretty strong debris flow signals on RER that even shows up on the spectrograms of OBSR and weakly on several other stations. This may have been the largest thus far…. at least large for shaking the ground. It seems to have started about 00:24 Z 9/13/2015 (5:24 PM PDT 9/12/2015), jumped up strongly at 00:29, peaked around 00:32 and back to almost background by 00:50 Z. Here are spectrograms from stations STAR, RCM, RCS, RER, FMW, OBSR, PANH and WPW for the period 00:20 to 00:55 Z on Sep 13.

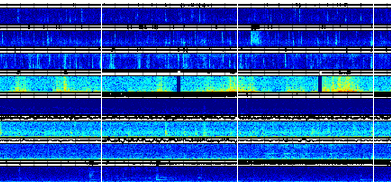

There were also some different sorts of signals in the evening and into the night with bursts getting stronger from time to time until after midnight local time. These signals are different than the ones we typically associate with debris flows that are fairly broadband on RER. These different signals in the night had a stronger low-frequency component yet they did not show up on any other stations. This is strange since low-frequency signals attenuate with distance at a lower rate than do high-frequency ones and thus one would expect them to record well at other stations. My totally wild-ass guess is that these may be due to slumping of stream walls very near the RER station after being undercut by the debris flows earlier in the day; however the could just as likely be due to trees near the site swaying in a breeze. Here are the spectrograms for a sample of these events from 07:00 to 07:34 Z that same evening from the same stations.

In the CVO Hot Stuff archives you can find a report on a Mount Hood debris flow on Sep 3, 2015. On Sep 12 and 13, 2015 there were several times when weak broad-band signals on stations PALM, TMB and, to a lesser extent on HOOD, show the characteristics of small debris flows. Here are spectrograms of those stations for the period 21:05 to 21:55 Z showing the debris flow signal peaking around 21:25 Z.