Mystery Booms and Forensic Seismology

There is now a podcast interview with Steve Malone on this topic by KUOW's Soundside series.

A little over a week ago a colleague and retired seismologist, Tom Owens who now lives on Orcas Island in the San Juans sent a note to the PNSN about being awoken in the early morning of March 7 by a loud boom. This is the second such event in the last few months for Owens, who heard a similar boom, accompanied by a flash seen from his bedroom window back in December. Even though retired, he was also now awake, annoyed, and curious if the boom was recorded on the PNSN seismic stations in the San Juan Islands. Sure enough a sharp, short pulse of seismic energy can be seen on the records at about the time he was awoken. However, he observed that the energy was moving across the network at speeds much slower than expected for seismic waves. Owens forwarded his observations to us wondering if we had any thoughts on what could explain them.

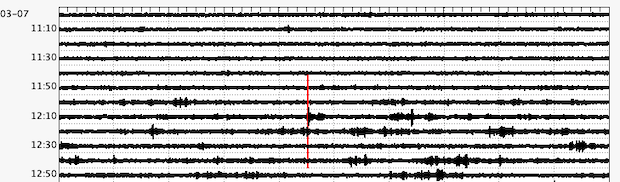

Fig. Part of seismogram from station, ORCA on Mar 7, 2022. Note short strong signal (red) at 12:14:30 GMT (04:14:30 PST).

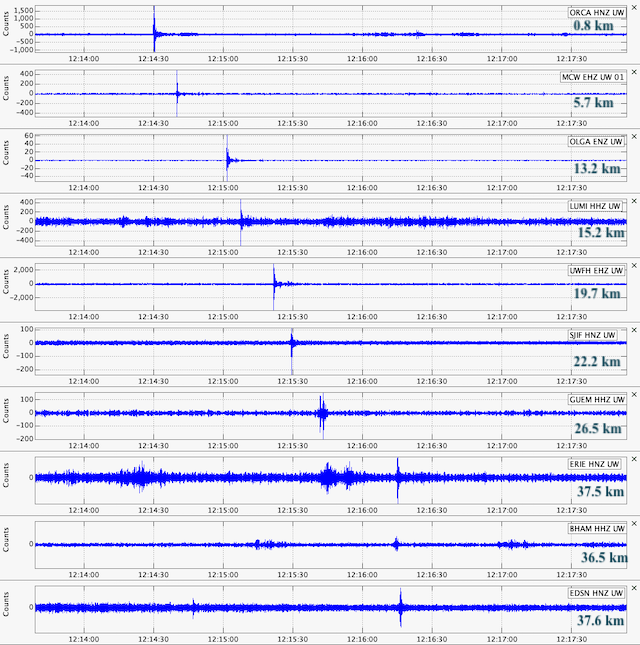

Being interested in exotic events (non-earthquake shakes) I looked at all the seismograms for all instruments located in the general area. Wow! This was well recorded on many stations, enough that by determining the time the pulses arrived I could get an approximate location for the source of the boom. Looking at the “move-out” of arrivals (time versus approximate distance) it was immediately obvious that this was NOT a shaking source in the ground. Owens was right. The slow move-out of arrivals was consistent with the velocity of acoustic (sound) waves in the air. By using a simple velocity model for air of 0.325 km/sec (727 Miles/hour) and measuring the arrivals of the boom on 10 stations to within a half a second I get a location for the source of the boom near the ground surface at: 48.6986 N 122.8923 W plus or minus about 1 km. This puts it near Crescent Beach Preserve just east of Eastsound.

Fig. Seismograms of the 10 nearest operating seismograph stations for several minutes around the mystery boom. The amplitude scales are arbitrary and adjusted so that the signals show up clearly. The distances away from the source are indicated on the right.

For a relatively small explosion to be this clearly recorded up to distances of 37 km (23 miles) means that the atmospheric conditions must be just right. There must be little wind and a stable atmosphere without large temperature gradients, at least within a few thousand feet of the surface. Looking at weather data for this period confirms winds of less than 2 meters/sec and relatively constant temperature with altitude.

The above analysis is very simple and straightforward. However, in this case determining what the explosion source was is not so simple. We first rule out natural sources and then, if man-made, is it legal and if not was it a potential crime. Here is where exotic seismology changes into forensic seismology (ie using seismology to study a potential crime).

A common natural source that can produce a boom is a meteor or fireball. We are quite familiar with these sorts of sources and have studied them in the past. In 2018 a bolide exploded off our coast and in 2013 a similar source was recorded in far eastern Washington. Such events take place high in the atmosphere and have a very different and much wider area of being recorded. It turns out that a tweet from someone in Bellingham includes a short video of a bright meteor falling in the area at “about” the right time. However, it is 15 minutes later than the boom and the originator confirmed that his clock is accurate. Searching the seismic records at and following the time of this video there are only a couple of possible very small signals that could be attributed to it. So our mystery boom was not a high atmospheric explosion.

What about man-made sources? We have lots of experience with man-made explosions. Of course there are many mining blasts in the region, sometimes several per day. Since these are designed to break rock we easily record the seismic signals from these but sometimes also the acoustic airwave if the explosion is at the surface. When a quarry or mine first opens it is sometimes hard to determine if a recorded signal is from an earthquake or quarry blast and sometimes even very distant but large ripple fired blasts fool us for a while. One thing that guarantees the mystery boom is not such an event is that all commercial blasts must be during daylight hours.

What about military exercises? Again we have experience detecting and recognizing both artillery practice and super sonic aircraft. The latter is quite easy to recognize by the shape of the cone of sonic booms generated. There are many reports of sonic booms heard (that sometimes are confused with thunder) and we have infrequently recognized signals as due to true sonic booms by their characteristics. We used to call various military airbases and inquire about their flights. We were always told that there were no operations scheduled for the time we saw the signals. Of course some of these (maybe most) were secret missions and if they had confirmed that their planes had made them then they would have to kill us to preserve the secrets. In any case our mystery boom was definitely not a sonic boom.

We also have some experience detecting and locating accidental explosions in urban area, one in north Seattle and one in Port Orchard that resulted in fatalities. The exact locations of both of these were known. Using our seismic data we obtained locations within a few hundred meters of the known locations.

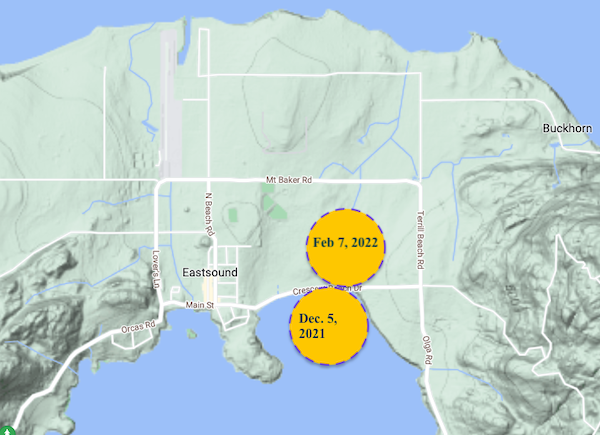

So what were the mystery booms? It seems that the local newspaper and social media from folks on the islands have reported more of these night time booms. We got a list of dates and times and searched the seismic records for many of these and could only find one clear case that looked similar to the one on March 7. This was a boom at 12:49 GMT (4:49 am PST) on Dec. 5, 2021. It seemed to be a bit smaller and the approximate location puts it slightly south of Crescent Beach out in Ship Bay. However, the error estimates on this location are large enough to have it back on land near the same place as the Mar 7 event. We could find no obvious seismic signals at the times of other reported booms. Only in the last few months have additional seismic stations been installed in the San Juan Islands so our observation ability is improving with time. At this point we are left with explosive sources that are probably not legal for at least some if not all of these booms.

Fig. Map of the Eastsound area of Orcas Island showing the rough locations of the two booms that were pretty well recorded by PNSN seismographs. The uncertainty of the locations are about twice the size of the circles so it is possible they were in the same place.

Of some concern are reports in social media of the remnants of pipe bombs being found in remote parts of Orcas Island. The early morning times and no one taking credit for these booms makes them seem less than innocent. The local sheriff’s office has been investigating similar reports in the past and is interested in determining what is going on so anyone who has information should contact them (360) 378-4151 or the anonymous tip line: (360) 370-7629. Our seismographs may be able to help locate events if we know what time on the records to look. However our automatic detection computer programs are trained to look for earthquakes and, as explained above, these booms produce very different looking seismic records and thus are not easy to automatically detect. If you hear any strange night time booms send us an e-mail with times and general area heard and we can follow up to see if they were seismically recorded and maybe we can pin point their location. E-mail to: <pnsn@uw.edu>.

Help with this study came from Tom Owens (retired seismologist and professor, University of South Carolina), Mickey Cassar (seismologist and field engineer with the PNSN) and Paul Bodin (retired seismologist and former manager of the PNSN).